In March of 1941, Captain America exploded into the 3-color world at Timely Comics draped in the American flag. Born from the minds of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby as a way to bolster pro-war sentiment at a time when the U.S. was doing everything they could to stay out of “that fiasco in Europe.” (and to compete with

The Shield appearing the pages of Pep Comics) The first cover of Captain America Comics #1 depicted ol’ wing head punching Hitler square in the jaw, a full year before Pearl Harbor. Their gamble seemed to work on the minds of the public, since each successive issue sold nearly a million copies, with those numbers holding solid throughout the war. Throughout his enduring career, his popularity has risen and languished but at his peaks he has been a soapbox of political commentary from his writers and artists.

The WWII years were filled with Captain America punching Nazis and fighting Hitler’s right hand man: the Red Skull (a man who is possibly the most evil bellhop in history!). Joe Simon and Jack Kirby left the book after issue 10, but the book continued unabated. When issue 12 hit, Pearl Harbor had just happened and Captain America gained a whole host of new Asian themed villains… that looked horrifyingly like yellow skinned vampires.

There was no call for political correctness, this book was unapologetic propaganda and it received no slap on the wrists for it. But these days could not last, as the publics’ tastes would soon change.

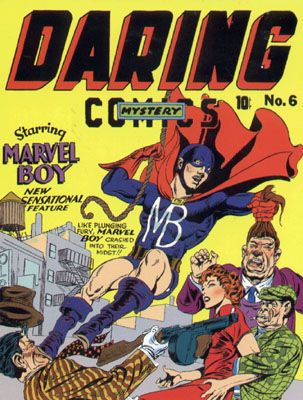

Immediately following WWII, super-heroes seemed unnecessary to the general public and supernatural horror became the status quo. The people at Marvel quickly shifted Cap’s tone to fit the market, retooling it into Captain America’s Weird Tales. Retooling it so much in fact, that the final issue of Captain America Comics (#75, Feb. 1950) did not even have the star-spangled hero within its pages.

But the book was still given the axe after only two issues due to mounting backlash against horror comics from the public at large. After a three-year hiatus, Marvel (at that point known as Atlas) tried to revive Captain America as “The Commie Smasher” in hopes that Super-Heroes would make a comeback as the horror genre died. This endeavor proved fruitless and the series was canceled again after only three issues. Captain America was not seen again in comics for nine years.

When the Silver Age ushered in a rebirth of the superhero genre, Stan Lee had Cap thawed from a block of ice by Marvel’s preeminent superhero team the Avengers. This long absence, and displacement from time has since become a core part of Steve Roger’s character. “Out of touch with his time” but still in touch with the country’s fundamental core values, he acted as a living reminder of what America stands for.

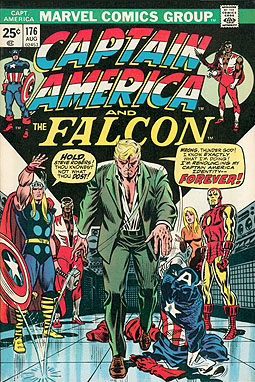

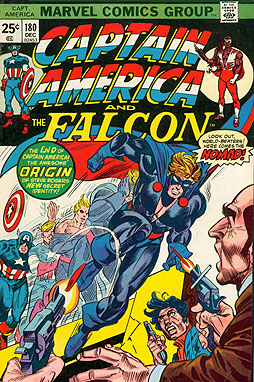

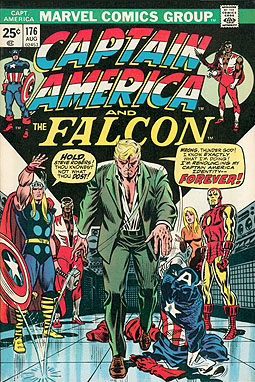

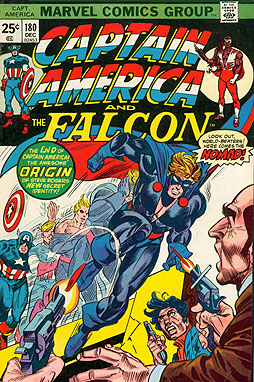

During the 1970s, the Watergate burglary and the Vietnam War was fast diluting America’s stalwart idealism and Englehart was in the right place at the right time to write some of the most innovative and daring stories since Captain America took on “the yellow demons of the East” after Pearl Harbor. One of the first long form stories in Marvel history, Englehart took Captain America on a journey from patriot to disillusioned vigilante, and back again (#169-186). For nearly ten issues (#176-184), Captain America gave up his costumed persona. His co-star The Falcon became one of the first major black characters to have a “leading” roll in a comic book. Steve Rogers meanwhile, was acting as Nomad trying to find out who was responsible for a criminal conspiracy which lead him all the way to the White House. There, he confronted the President himself.

Immediately following Englehart’s departure, Jack Kirby returned to the book that made him a super-star all those years ago. Just in time for the country’s bicentennial! An 84 page treasury issue was commissioned entitled “Bicentennial Battles” which told the tale of the ominous Buda transporting Cap through time witnessing the glory of every major American conflict throughout time. It was a simple idea, but a real showcase for Kirby’s talent as an artist. Handling Captain America in Western, War and Sci-Fi genres with inks by the likes of Herb Trimpe, John Romita Sr. and Barry Smith. With Captain America returned to his heroic best, and the country returning to a sense of wide-eyed wonder and excitement, it seemed as though there was little for him to protect the people from.

The wide-eyed wonder brought on by the copious amounts of drugs consumed in the 70s became a target of President Ronald Regan’s massive war on drugs. Virtually every kid’s icon was recruited at one time or another during his administration to be apart of some cheaply produced PSA warning children of the dangers of drugs. And Captain America was not immune. Marvel was also selling off his likeness to video game companies and toy companies. He had fought through the Englehart era and those Bicentennial Battles just to be turned into a plastic puppet of the government he was trying to unmask.

But in those “me” centric times of Regan and Bush, there was little use for a hero of Captain America’s ilk once more. People used Captain American as a broken idol in their music instead of reading his title. The comics became mired in histrionic re-treads of basic civics lessons told in roid-raged battles. The Nomad story was re-imagined 20 years later with Captain America retiring to be “The Captain” and the government replacing him with a more politically conservative soldier named U.S. Agent. His replacement went insane from the pressures of being Captain America in the stories conclusion. The book’s strength has always been during times of crisis, and his best decade was just around the corner.

“The Oughts” were a politically charged era. Between 9/11, the Patriot Act and the discovery of torture at Guantanamo Bay, the people at Marvel were handed a wealth of story to sew an impressive re-imagining of Old Glory. The Bush administration started with the fall of the two towers. The U.S. was in shock, and the Bush Administration wanted blood and John Ney Rieber preached peace in the pages of Captain America. He showed Steve Rogers helping with the clean up at Ground Zero, wallowing in his hatred for the people that attacked his country. Then he intervenes in a fight that breaks out between a New York native of Middle Eastern decent, and a man who lost his daughter that day rendered nearly photo-realistically by John Cassaday. Realizing his hatred may be misplaced, Captain America softens and thinks about how we need to be united against whoever the enemy is and not blindly hating one another.

The book continues with Captain America meeting terrorists from the Middle East and learning of their reasons for hating America. Not justifying what occurred, but merely showing the other side. Rieber also gives a mind-bending history lesson showing Captain America all of the atrocities America has committed. Given the history of the character, one would assume that he would now retire the costume again, become a terrorist and fight the United States with some new codename. But instead, Steve Rogers unmasks himself on television and says he will no longer hide his identity. He has realized that we should hold individuals accountable for their crimes, not entire nations. Some papers proceeded to brand Captain America as a traitor and that these comics should not be sold to kids (Medved). Their complaints fell on deaf ears at Marvel as they soldiered on with Captain America preaching a message of responsibility and compassion in the face of blind hatred, quite different from the ideology of the Kirby era.

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 (Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act) was enacted. This act reduced many privacy rights that foreign citizens possessed within the United Sates, and also made it much easier for law enforcement to search homes without telling the occupant. So Marvel’s writing staff concocted a big event for 2006-2007 as a large-scale satire, the event was dubbed: Civil War. This event spanned every title in the Marvel universe, everyone fought everyone, and many heroes died. It was concocted as a massive allegory for the Bush administration from beginning to end.

After super powered beings cause a catastrophe akin to the events of September 11, the U.S. Government enacts the Superhuman Registration Act. Which stated that all superhumans are required to register their true identities with the U.S. Government. And act as government agents around the world. Iron Man takes the diplomatic step and becomes the government spokes person, while Captain America leads a rebellion against registration. Even though he himself was a registered government office whose identity was a matter of public record, Captain America thought that the Superhuman Registration Act was a true invasion of privacy, and forcing any superhuman to act on behalf of the government put too much power into potentially the wrong hands. If the superhumans did not comply they were placed in an extra dimensional prison devoid of their rights and civil liberties. This major event concluded with Steve Rogers being assassinated while he was approaching the courthouse to stand trial for defying the government and fighting against Registration. Marvel’s President Joe Quesada has said, “There’s a lot to be read in there. But I’m not one who’s going to tell people this is what you should read into it.”

The title has continued after the death of Captain America, with his former sidekick taking up his mantel and his old partner The Falcon fights alongside him. The book’s message continues the idea of political commentary that made it so famous in the past three years. Ed Brubaker writes stories about The Falcon and the new Captain America as they tour the country trying to hunt down homegrown terrorists. In a recent issue, people were protesting taxes in a large rally. They were carrying signs that are common at Tea Party rallies. Brandishing slogans like “Tea Bag the Dems.” In story, some white supremacists infiltrated the group and the two heroes were going to uncover them and bring them to justice. The real life Tea Party organization took offense to this, demanding Marvel apologizes for defamation of character, and stated that they were not a racist organization. In an unprecedented moment, Marvel folded and apologized for mentioning the Tea Party. They went on to blamed the letterer for the error and that all subsequent printings would have the offensive sign removed. (Picket)

It’s hard to believe that a company and a character with such a long legacy of letting its writers speak their minds would be so quick to cover their tracks and place blame. It seems as though the world has a different Captain America after all.